By Natasha Lunn*

I used to think that loving someone meant knowing everything about them. Every mole on their back, every childhood memory that left a mark, every corner of their mind, however dark. I longed for these precious pieces of knowledge, to be trusted with them, and to trust someone with the pieces of me in return. I longed for them for the same reason we often long for things: because we lack them in another place.

At the time, my relationships were sustained by the opposite of knowledge, by concealment: stories not told, feelings unexpressed, opinions withheld. And so, in a quiet place in my mind where I knew I wanted intimacy and this wasn’t it, I dreamt of knowing every beat of another person. Of a place where nothing was held back, not a single thought left unshared.

Now I know that intimacy doesn’t work like that. Not really. It does require us to share stories, feelings and opinions. But it also asks that we find the courage to accept that there are some parts of another person — and of ourselves — that we will never know entirely. As much as it is about intimately knowing someone, love is about accepting the mystery in each other too. Not being threatened by the pieces of a partner or friend that are beyond your reach, and instead seeing that these unknown parts are what allow for mystery and beauty and newness, even after decades of knowing a person. What a gift!

Still, this mystery can make sustaining love more complex. Every time we figure out what we need, or what another person needs, we change and surprise each other. Whenever we fix an assumption about a friend or partner, we risk of overlooking who they are today. With these challenges in mind, I decided to turn to psychotherapist Charlotte Fox Weber — who has been a therapist for over a decade and also founded The School of Life Psychotherapy — to find out how we can work on what she calls ‘recasting ourselves,’ and on allowing the people we love to recast themselves too…

What is the most common issue for couples who come to see you in therapy?

A lack of freedom. It comes from a range of sources: a lack of financial freedom, of emotional freedom, of time. When we commit, we like to lock love down, but then we feel restricted. And we don’t always realise how much freedom we’re giving away when we sign up for certain things, whether it’s having children, moving into a house, getting married, or saying, ‘I’ll be the breadwinner’. We don’t see how much those decisions are going to cost us at another point. And then, it becomes a problem.

So we want the security of the commitment, without losing the freedom?

Yes, we’re contradictory: we want to feel safe, but security can also be restrictive. Then we can then blame the other for our lack of freedom, when actually, a lot of the time we hold the keys to our own release. We can have a degree of autonomy and we can take charge of our own freedom. The other person is not a prison warden, but, if we feel restricted, we can hold them accountable.

Do you think, then, it’s useful to help individuals see that they are more in charge of their own freedom, and to not solely blame their partner?

Absolutely. Responsibility is important. That doesn’t mean you’re entirely on your own, but being able to negotiate and take charge of yourself can go a long way. Sometimes, drawing attention to the freedom issue can open up a conversation. But often, couples come to therapy describing discontent, or a crisis, when actually those complaints are veiled desires. They’re describing a resentful dynamic, blaming each other, instead of saying, ‘Oh, it’s that I want freedom.’

What’s an example of something that might be a complaint on the surface, that is really about freedom?

A woman enjoys cooking for her husband and keeping a beautiful home. Then they have a child, and she finds herself feeling unnoticed, unappreciated for the things that used to give her joy. She realises he can’t cook for himself and she’s in a 1950s situation. There are so many couples that come to mind with this example. And it’s fascinating that so many feisty, formidable women cook for their husbands every night. Often that habit came about because it brought joy at one point — she loved cooking, he’s a rubbish cook — but now she feels obligated. What was once a desire has become a burden, an expectation, and she feels trapped because there’s no flexibility. On the surface the complaint is she’s aggrieved. She’s ticking boxes on an endless to-do list, with no time to herself, and her husband doesn’t notice. But when you look at that to-do list, it started out as something very different.

I think about this a lot, because my husband enjoys cooking and is better at it, but I still make an effort to cook, because I don’t want to slip into depending on him to make every meal for me. Then he wouldn’t enjoy it and I would never improve. I used to think you should play to each other’s strengths, but now I think, even if you’re bad at something, it’s important to keep swapping roles.

There’s something called role function that happens in group dynamics, where you get sucked into a role. It’s a problem if it becomes fossilised and inflexible. Something I encourage with couples is fluidity in those dynamics: being able to update your roles and responsibilities. They should be reviewed periodically – in relationships, work and in almost every situation – because we change, and things creep in. So being able to negotiate your collaboration is essential. It’s not that it’ll be 50/50 in every moment: one person might take on more financially, or domestically. That’s fine at one point, but there should always be an awareness that it can be reviewed over time.

What you said about role function in a group dynamic reminds me of friendship. Because in groups when I was younger, I would often assume a childlike role: I wouldn’t cook or choose what we’d buy in a supermarket on holiday, I wouldn’t contact the landlord. But in my newer, adult friendships, I am more practical, and take the lead in some situations. Those recent friendships have helped me see that I do sometimes like taking charge and caring for people. And it’s freeing to be understood in a different way.

Completely, and to develop and grow. One of the things therapy tries to help with is being allowed to recast yourself. Again, a lot of it comes down to freedom and being able to take charge of yourself. We need to accept that people won’t feel exactly how we want them to — that is true with partners and friends. You can negotiate dynamics and change, but don’t expect that to be immediately seen and validated. Know it for yourself instead. Because you can own your space and say who you’ve become, but you may still be typecast in a way that doesn’t feel entirely accurate. Surviving that can be hard, but it’s also almost inevitable in friendship groups.

That’s interesting, because when I was younger I was more insistent about my personality, my politics, my music taste. I was desperate to assert myself, and I now wonder if that’s because I wasn’t sure who I was.

We want from the outside what we’re missing on the inside. That’s one reason there’s anxiety about proving something at school reunions, and saying, “Please see me as a different person from how I was unfairly seen back then.” Demanding that validation is a lot of pressure. But I think it’s important to assert those boundaries. So, if you’re in a dynamic with a friend and you want to reposition yourself…let’s say, for whatever reason, at one point you picked up the bill and you want to change that. You could decide that you’re going to go 50/50 going forward, but you don’t need to necessarily be a truth crusader and have a full discussion about it. You can assert yourself and split the bill, but you don’t have to say everything.

It comes back to realising you’re more in charge of how you respond than you might assume. So, in my old friendships, instead of feeling pigeonholed, I could have said, ‘I actually want to choose what to cook today,’ rather than accepting the other role.

Absolutely. It’s advocating for yourself. Because we can slip back or regress to playing our former roles. And actually, rather than freaking out that people still see you in a certain way, there are more subtle ways of showing people who you’ve become.

Thinking about how to sustain friendships, do we need to find new ways to introduce consistency as life pulls us apart, or is it more about accepting their fluidity?

Societally and culturally, there’s no narrative arc for friendships the way there is for romantic relationships. They are not legally recognised, there isn’t the same commitment, even though we know they matter. For instance, take psychotherapy intake forms. You find out about the person’s family history, but you don’t have a list of their friends, and you probably should.

Monogamy is not an expectation, either; you’re allowed to be promiscuous with friends. Its joyful to have that freedom: friendship can be wonderfully plotless and that’s part of its charm. You can choose when you see friends, it’s not fixed. But that lack of commitment means you can neglect each other more easily.

Given we don’t assign labels to friendship in the same way, how can we bring more commitment into it?

By recognising its high value. Sometimes it matters as much as eating a meal. It might sound selfish, but there are times where I’ve prioritised friendship over my children, my husband, my work. I’ve allowed it to matter. Not all the time, but for instance, the other day I felt I needed to have a conversation with a friend more than anything else in the world, and I took it seriously. I completely prioritised it. And it is about priorities, not just thinking, ‘Oh, theoretically friendships matter, but everything else comes first.’ Sometimes it has to come ahead of everything else. It’s about being able to discern when that’s needed.

But are you only able to do that with a smaller, closer group of friends?

Well, to quote Joyce Carol Oates, we have to be custodians of our time. You could fritter away all your time keeping up socially. So being discerning matters, and with close friends, it’s not about meeting up all the time. It’s about tolerance: allowing and forgiving for time periods when you don’t see each other as much. After all, socialising is different from having friendships. If you’re a people-pleaser, and you feel you have to meet up with a friend or you’ll be in trouble, then that’s a problem. Flexibility is everything, in friendships and romantic relationships. What doesn’t bend may break, so being able to bend is important. You have to learn that there can be absence and distance, and that you’ll come back together.

So in the years when you’re not able to see them all the time, how can we continue to prioritise friendships?

You have to find other ways to show interest. Sometimes that could be a placeholder message. It’s hard to give a heads up that you’re not going to be available, especially if you are a people pleaser. But being realistic and preparing people – and yourself – can be helpful. Saying, ‘I’m not going to be able to see you until July.’ This is what I’ve had to say to certain friends: ‘I’m not going to be available until I’ve handed in my book manuscript.’ It took me a long time to take myself seriously enough to say that, despite the guilt and conflict. But sometimes if I get a message from a friend saying, ‘I’m horribly overwhelmed right now. I love you, I miss you, we’ll talk soon,’ I really appreciate it. Even if you don’t have enough time to properly catch up, just sending out a placeholder of affection helps. It doesn’t mean that you’re fully caught up and know everything that’s happening in each other’s lives, but it’s a signal of love and attentiveness.

With old friends, a lot of the time you don’t experience as many new things together as you age, and you retell old stories. Why do we do that?

It’s a reminder of our former selves. And friendships are like storage facilities for who we were. We rehash stories because we are looking for that thread of connection, of continuity. Having shared memories goes a long way; we feel our past isn’t completely lost. Of course, it’s a problem when there are mismatched memories.

But is it important to create new memories with friends as we age, rather than relying on the old ones to sustain us?

There are different friends for different things. Sometimes you love a friend because they’re from the past, and you wouldn’t necessarily become friends now. I don’t think you need to force making new memories with them. It depends how invested you are in the friendship, but not every one has to be monumentally important going forward. You can keep friendships for certain parts of yourself.

For those of us who are romantic, there’s a fantasy of what friendships should be, where we imagined that we’d be best friends forever. Letting go of those expectations can be hard, but it can also be part of allowing the friendship to continue, by not expecting it to be everything. We have to allow for certain unknown things in each other. We have to tolerate the otherness of people. You might have a friend you adore in some ways, and in other ways she might not get you — she might fall really short when it comes for understanding what motherhood is like for you, or she might not get your husband. And that doesn’t mean it’s all or nothing.

What about when there is a conflict or rupture in a friendship? Why do you think we can find that so difficult?

There isn’t much discussion about rupture and repair with friendships. We know that couples fight, but fighting with friends is still incredibly awkward and hard, and part of that is a lack of accountability. Back to what you said earlier about commitment: if you fight with your spouse and you live together, there’s a degree of accountability where you have to face each other. There’s some pressure to resolve it. But when there’s a rupture in a friendship, you may never see each other again if you don’t make a plan to, because there isn’t the same accountability.

I think the biggest threat to friendship is judgement, which is often a response to change. We usually judge when we don’t understand something, or when we envy something. That doesn’t mean there’s no place for it, though, because if you find yourself insurmountably judgemental of a friend, and you can’t get past it, it may be a sign it’s time to move on.

How can we tell the difference between judgement that is a sign the friendship’s not working, and judgement that comes from our own longing or lack of understanding?

By being brutally honest with ourselves. When I feel judgemental of a friend, I try to think, ‘What is going on?’ Am I actually envious? And if I’m envious, can I deal with that? Or am I appalled because there’s something that feels incongruent with my values, and can I get past that?’ Rather than expecting the friend to solve that one for you, ask yourself questions about what’s going on. I’m in favour of honest conversations, but it starts with ourselves.

It’s annoying in that the more I learn about love, the more responsible and accountable I realise I am!

Friendships can be saved when you are brave enough to speak up. We sometimes avoid conflict with friends and trash them instead. Like the money example I gave earlier. Friendships die over those things, because rather than allow the uncomfortableness of splitting the bill, instead, you grow apart. You think, ‘I don’t want to see that friend, because I’ll end up paying for the meal and I’ll resent that.’ We make it binary for ourselves – either the problem gets completely solved or I’m walking away – rather than speaking up.

Sometimes it’s not even a rupture. You just feel more different from a friend as time passes, because they only know certain parts of you today. And perhaps that’s okay.

Absolutely. When we expect one person to be everything, in any context, that’s a problem. You must have friends who you can talk about your writing with? But other friends might not be interested in that. They might not want to learn about you from reading you. It’s important that we don’t set traps for friends, and historically I have. So if a friend really loved me she should do this, or if we’re really good friends she shouldn’t do that. Actually, letting go of those rules is important. Otherwise, we’d be left pretty isolated, because people fail those little tests all the time.

What do you wish you’d known about love?

I wish I’d realised sooner that love is about closeness, but it’s also about tolerating the gap between all people. It might have spared me some heartbreak to understand that we can still engage and connect and be close, but respecting otherness is really valuable. When we can accept that we don’t know everything about each other, or ourselves, then we can remain open to experience.

*First published in Natasha’s Conversations on Love Newsletter.

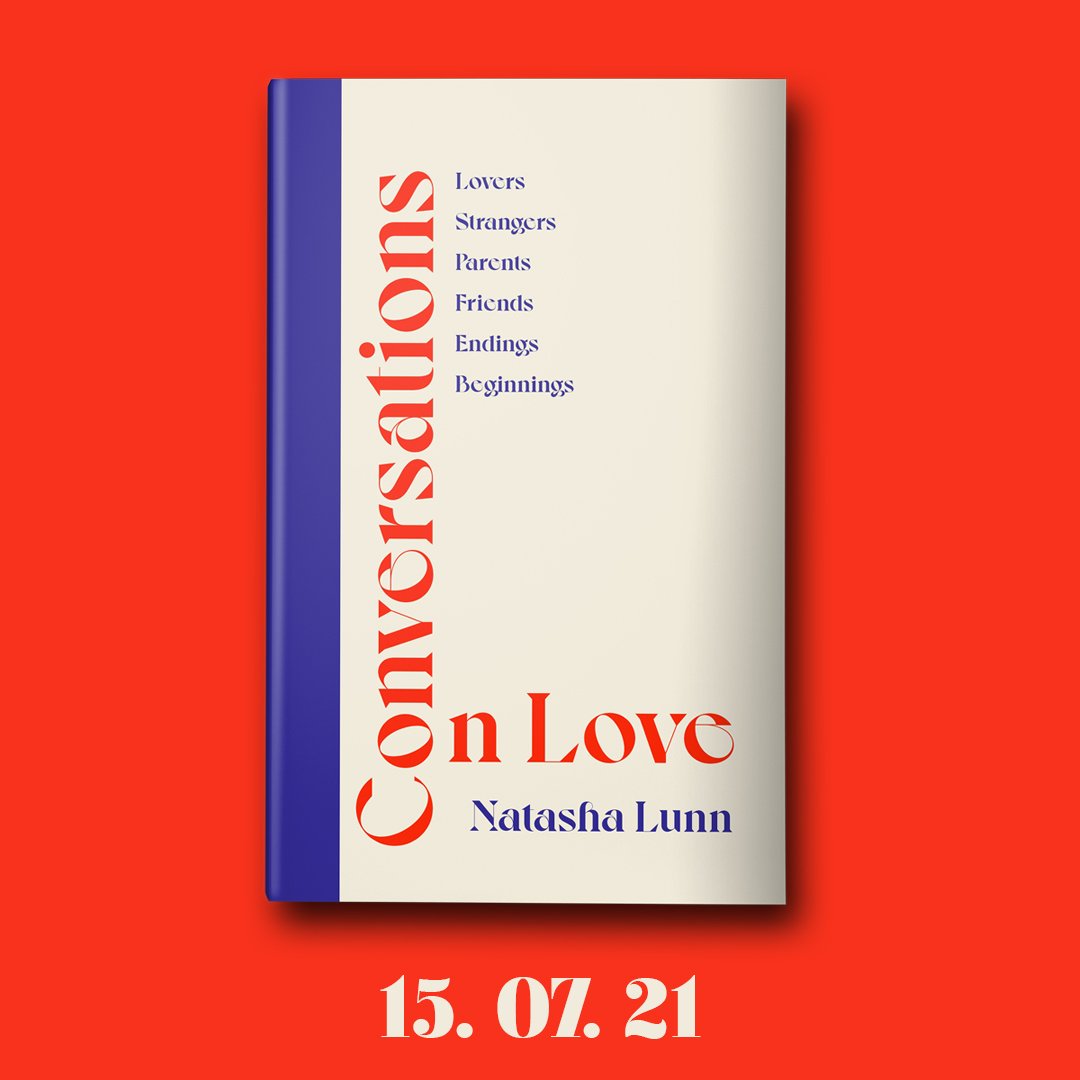

** Natasha’s book Conversations on Love is coming out next month! Pre-order a copy here.

About the book: After years of feeling that love was always out of reach, journalist Natasha Lunn set out to understand how relationships work and evolve over a lifetime. She turned to authors and experts to learn about their experiences, as well as drawing on her own, asking: How do we find love? How do we sustain it? And how do we survive when we lose it?

In Conversations on Love she began to find the answers:

Philippa Perry on falling in love slowly

Dolly Alderton on vulnerability

Stephen Grosz on accepting change

Candice Carty-Williams on friendship

Lisa Taddeo on the loneliness of loss

Diana Evans on parenthood

Emily Nagoski on the science of sex

Alain de Botton on the psychology of being alone

Esther Perel on unrealistic expectations

Roxane Gay on redefining romance

and many more…